Psoriasis, Inflammation, Anxiety & Depression: What the Science Is Teaching Us About the Brain–Body Connection

A 2025 review by Keenan & Granstein in Acta Physiologica offers a powerful and evolving perspective on mental health: anxiety and depression are not “just in the mind.” They are deeply connected to immune signaling, inflammation, and neurobiological pathways that link the skin, brain, and nervous system.

For those of us practicing modern psychiatry, this research reinforces something we are learning more clearly each year — mental health is systemic.

The Article’s Unique Perspective

Keenan and Granstein (2025) explore how proinflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β) and neuropeptides (including substance P and CGRP) play roles in:

-

Psoriasis

-

Depression

-

Anxiety

Psoriasis has long been understood as an inflammatory autoimmune skin condition. However, this review highlights how the same inflammatory mediators active in psoriasis are also implicated in mood and anxiety disorders.

Cytokines & Mood

Proinflammatory cytokines can:

-

Cross the blood–brain barrier

-

Alter serotonin and dopamine pathways

-

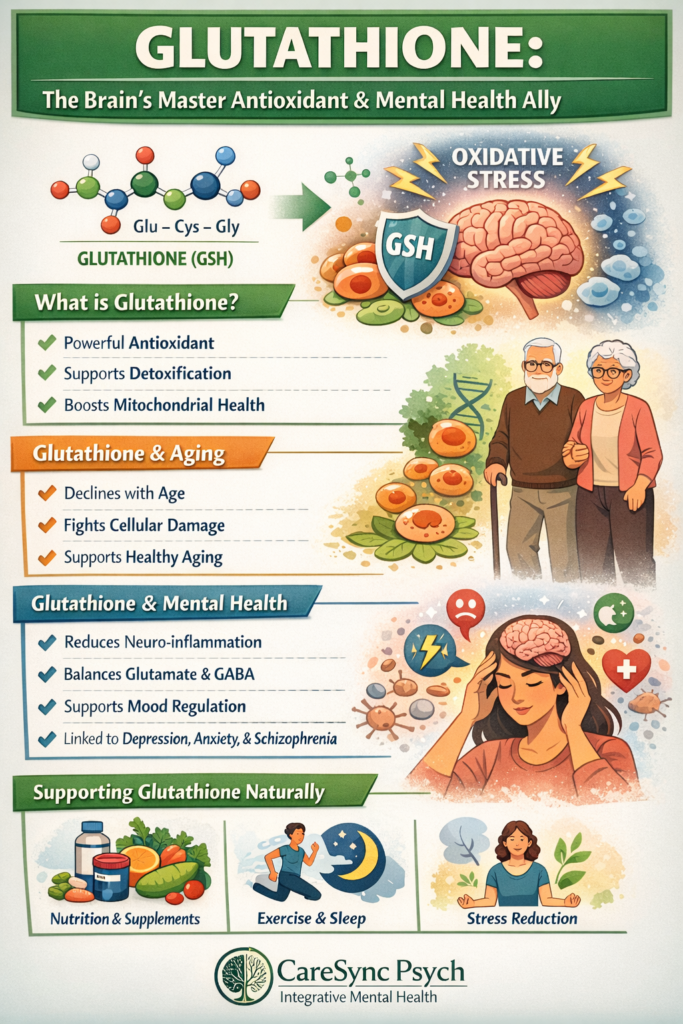

Affect glutamate signaling

-

Activate the HPA axis

-

Increase neuroinflammation

So the result can cause symptoms that look like depression and anxiety — low mood, fatigue, sleep disruption, irritability, brain fog, and heightened stress reactivity.

This helps explain why:

-

Patients with psoriasis have higher rates of depression and anxiety.

-

Patients with chronic inflammatory conditions often report mood symptoms.

-

Traditional antidepressants sometimes only partially address symptoms when inflammation is a driving factor.

Psychiatry Is Expanding: The Brain–Body Model

For decades, psychiatry focused primarily on neurotransmitters. Today, we are integrating:

-

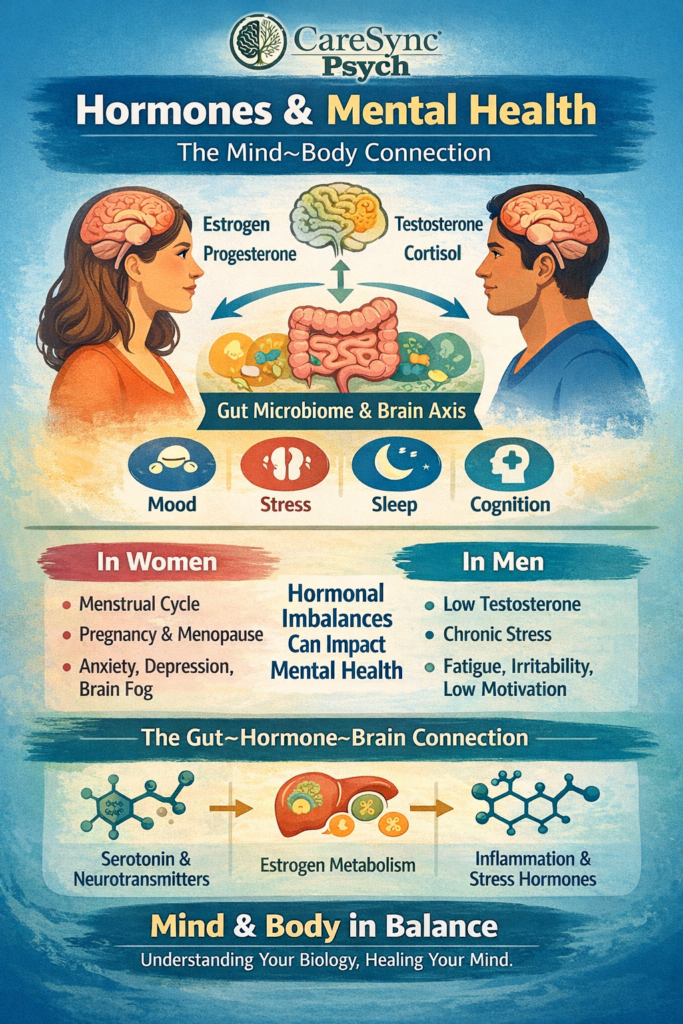

Immunology

-

Endocrinology

-

Gut-brain signaling

-

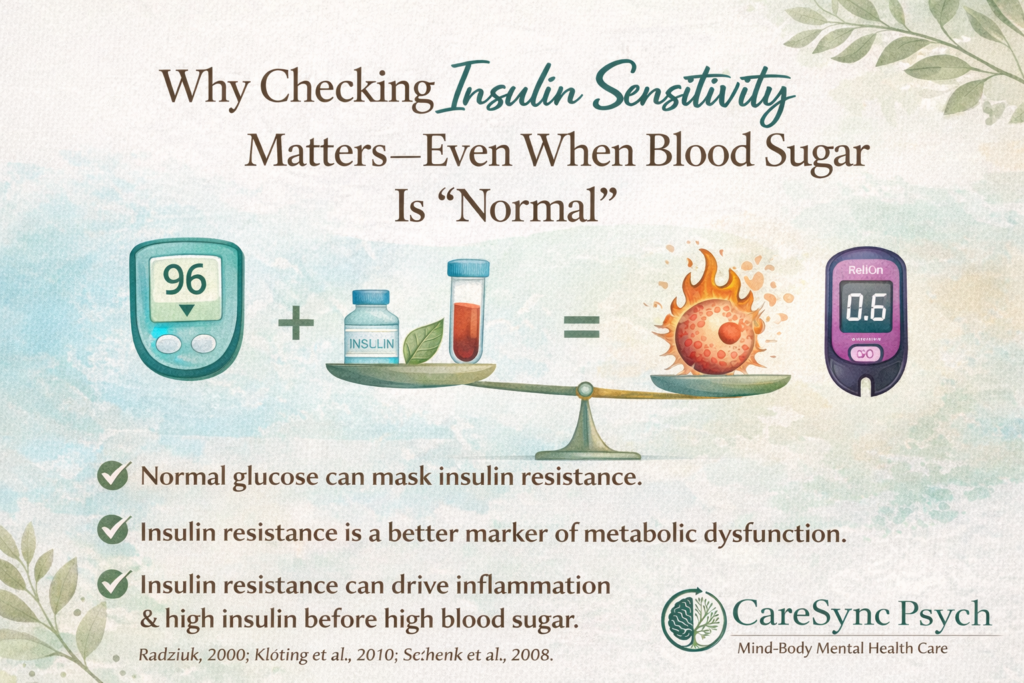

Metabolic health

-

Stress physiology

This article reinforces the concept of psychoneuroimmunology — the dynamic communication between the nervous system, immune system, and endocrine system.

At CareSync Psych, we believe in treating the whole-person, no just mental health.

Mental health is not separate from:

-

Autoimmune conditions

-

Hormonal shifts

-

Metabolic dysfunction

-

Chronic stress

-

Inflammatory load

The brain and body are in constant dialogue.

Why This Matters for Anxiety & Depression Treatment

Understanding inflammation’s role opens doors to more comprehensive treatment planning, including:

-

Lifestyle interventions that reduce inflammatory burden

-

Nutrition strategies that support immune regulation

-

Sleep optimization

-

Stress-response regulation

-

Thoughtful medication selection

-

Targeted lab evaluation when clinically appropriate

This does not mean inflammation causes all cases of depression or anxiety. However, it does mean that being to narrow or ignoring the body misses part of the story.

A Whole-Person Approach in Psychiatry

At CareSync Psych in Lakeland, Florida, we embrace this evolving science. We practice psychiatry with a brain-body framework, integrating:

-

Evidence-based medication management

-

Therapy and psychoeducation

-

Metabolic and lifestyle considerations

-

Personalized treatment planning

We are licensed to provide psychiatric care in:

-

Florida (FL)

-

Iowa (IA)

Telehealth available throughout Florida and Iowa.

Arizona (AZ) and Washington (WA) licensure pending.

If you are struggling with anxiety, depression, autoimmune symptoms, or stress-related flares, know this:

Your symptoms are not a personal failure. They may reflect complex biological signaling — and that means there are multiple pathways toward healing.

The Future of Mental Health Care

Research like Keenan & Granstein (2025) continues to move psychiatry forward. We are no longer separating skin from brain, immune system from mood, or stress from physiology.

The future of mental health care is integrative.

And it is already here.

CareSync Psych

Psychiatric Medication Management | Therapy | Brain-Body Mental Health

Lakeland, FL

Serving Florida & Iowa via telehealth

Arizona & Washington pending licensure

If you’re searching for:

-

Psychiatric provider in Lakeland FL

-

Anxiety treatment in Florida

-

Depression care in Iowa

-

Integrative psychiatry near me

-

Brain-body mental health care

We’re here to help.