The Brain–Gut Connection: What New Research Tells Us About Mental Health

Recent scientific studies are shedding transformative light on how our gut and brain communicate — not just in digestion, but in mood, cognition, and overall mental wellness. This gut–brain connection is becoming a central pillar in understanding resilience, stress regulation, and even neurodevelopmental health.

The Microbiome as a “Second Brain”

Research by Gwak & Chang (2021) highlights the role of the gut microbiome — the trillions of bacteria living in our digestive tract — in influencing the brain through immune, endocrine, and neural pathways. These microbial communities help regulate:

-

Neurotransmitter production

-

Inflammation and immune response

-

Gut barrier integrity

When the gut barrier weakens (“leaky gut”), inflammatory signaling can travel to the brain, which may affect mood and cognition. This underscores that maintaining gut health is not just physical — it’s deeply psychological.

Takeaway: A balanced microbial ecosystem may help support emotional regulation and stress resilience.

Synaptic Plasticity & Development

Damiani, Cornuti & Tognini (2023) expand this picture, showing that gut microbes can influence neuroplasticity, the brain’s capacity to change and adapt. Their work suggests:

-

Gut microbiota may impact brain development

-

Alterations in microbiome composition are associated with neurodevelopmental disorders

-

Microbial metabolites can modulate synaptic signaling

This research invites us to think beyond traditional psychiatry: early-life microbial exposures and diet might play a role in shaping lifelong mental health trajectories.

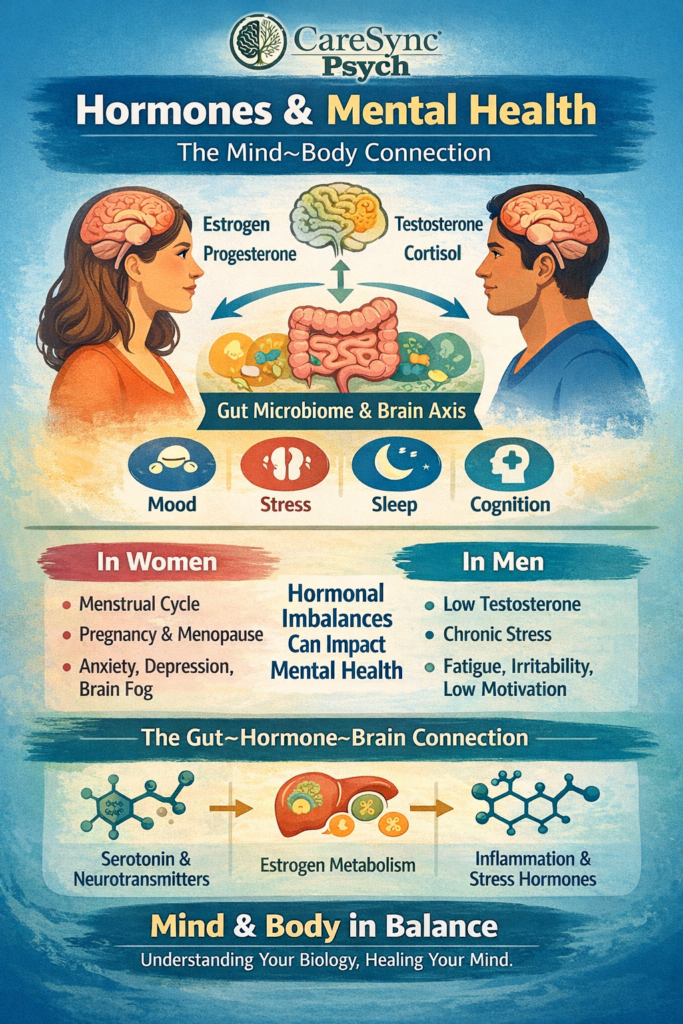

In a recent review, Manske (2024) outlines how gut–brain dynamics are relevant across the lifespan. Key points include:

-

Bidirectional communication through the vagus nerve and immune signals

-

How stress and mood influence gastrointestinal function

-

The potential for dietary and lifestyle interventions to support both gut and mental health

This integrative lens encourages clinicians and patients alike to value holistic care — from nourishing foods and sleep to stress management and movement.

A Future of Connected Care

As research continues to unfold, the brain–gut axis stands out as a bridge between mental and physical health — reminding us that healing pathways are interconnected. By integrating science with compassionate care, we can help people thrive both emotionally and biologically